From Blocking to Real-Time: WSGI vs ASGI Explained

Introduction

In the early days of Python web development, building a web application meant being tied to a specific web server. Each framework had its own way of working, and there was no common method for web servers and applications to communicate. This tight connection made it difficult to switch servers, reuse code, or scale applications smoothly.

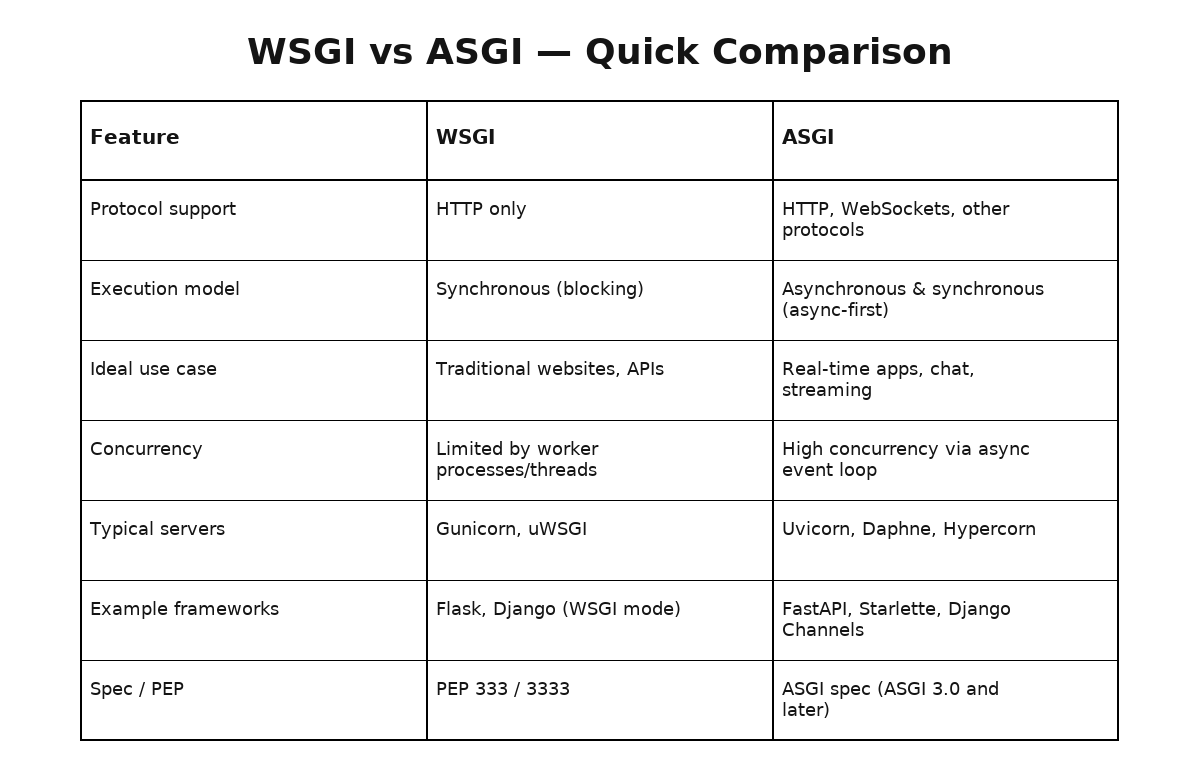

To solve this problem, WSGI (Web Server Gateway Interface) was introduced — a standard interface that allowed any Python web application to run on any WSGI-compatible server. It brought flexibility and consistency by clearly separating the web server from the application logic. However, WSGI only supports synchronous code and isn’t suitable for modern features like real-time communication or WebSockets. To handle these use cases, ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface) was later introduced, allowing support for asynchronous and high-performance applications.

In this blog, we’ll explore what WSGI and ASGI are, how they work, why they were introduced, and how they have shaped Python web development.

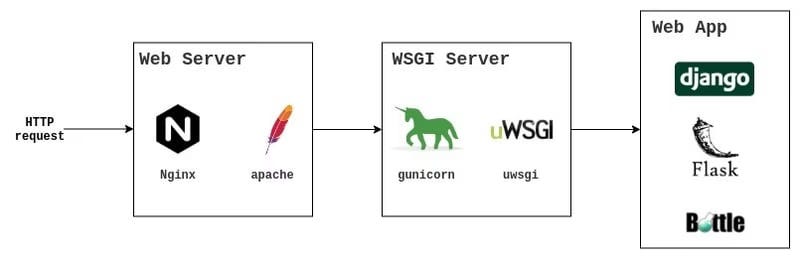

Web Server, Gateway Interface and Web Application

A web server is the software that connects a web application to the internet.

It handles incoming HTTP requests from clients (like browsers).

It serves static content (like images, HTML, CSS) directly.

For dynamic content, it forwards the request to a web application via a middleware server (like WSGI or ASGI).

Working of Web Servers

The browser sends an HTTP request (e.g., when a user opens a website).

A web server (like Apache or Nginx) receives the request.

If the request is for a static file (e.g., an image or HTML), the web server responds directly.

If it’s a dynamic request (e.g., a form submission processed by Python):

The web server passes it to a WSGI server (like Gunicorn, uWSGI) or ASGI server (like Uvicorn for async apps).

The WSGI/ASGI server calls the web application to process the request.

The web application generates a response (like a rendered HTML page).

The response is sent back to the web server.

The web server returns the response to the browser, which displays it to the user.

Gateway Interface

Gateway Interfaces act as a crucial bridge between web applications and web servers. They provide a standardized protocol that enables seamless communication between the two, ensuring compatibility and interoperability. By using gateway interfaces, different types of web servers can effectively connect with various web applications, making the web ecosystem more flexible and scalable. This standardized approach simplifies the integration process and enhances the performance and reliability of web-based systems.

Web Application

A web application is a software program that runs on a web server and can be used through a web browser. It contains the business logic, which means it controls how data is handled, checked, and responded to when users interact with it. Unlike static websites that only show information, web applications are dynamic and interactive. Users can do things like fill out forms, log into accounts, or get information from a database.

WSGI

WSGI stands for Web Server Gateway Interface.

WSGI is a Gateway Interface (GI) specifically designed for Python web applications.

It provides a standard way for web servers and Python applications to communicate, solving the earlier problem of tight coupling where only specific servers worked with certain frameworks.

With WSGI, any WSGI-compatible server can run any WSGI-compliant application, making deployments more flexible.

The interface was officially defined in PEP 333, and later updated in PEP 3333 for Python 3 support.

WSGI is built for synchronous and blocking operations and works only over the HTTP protocol, making it ideal for traditional, request-response-based web applications like blogs, content sites, or internal tools.

What is Blocking and Synchronous ?

In WSGI, synchronous means the server handles one request at a time for each worker.

Blocking means if something takes time—like reading from a database—the server waits until it’s done before moving on.

While waiting, it can’t do anything else with that worker.

Worker is a thread or a process that processes the incoming HTTP request and returns the response.

WSGI Code Example

Below is a Python script for creating a simple WSGI server. Let’s name this file: wsgi_server.py.

As a WSGI server, it has to accept the HTTP request from the web server (if the request needs dynamic response) .

Accepts HTTP requests from a web server (especially when a dynamic response is required),

Forwards the request to a Python web application by calling it with two arguments:

environandstart_response,Then returns the response generated by the application back to the client.

“”“

Simple WSGI Server

This runs your WSGI web application using Python’s built-in server.

“”“

from wsgiref.simple_server import make_server

from simple_wsgi_app import application

def run_server(host=’localhost’, port=8000):

“”“Run the WSGI server”“”

print(f”🚀 Starting WSGI server on http://{host}:{port}”)

print(”📱 Open your browser and visit the URL above”)

print(”🛑 Press Ctrl+C to stop the server”)

print()

# Create and start the WSGI server

with make_server(host, port, application) as httpd:

print(f”✅ Server running on port {port}...”)

try:

httpd.serve_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print(”\n🛑 Server stopped!”)

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

run_server()

wsgirefis a built-in module in Python’s standard library.It provides tools to create simple WSGI servers, mainly for testing or learning, and is not suitable for production.

from wsgiref.simple_server import make_server

from simple_wsgi_app import application

make_server()is a function that creates the WSGI server.The

applicationfunction (imported fromsimple_wsgi_app) is your web application.

The function make_server(host, port, application) takes three parameters:

host: The server address (in this case,‘localhost’since we’re running it locally).port: The port number the server listens on (e.g.,8000).application: The WSGI application function that handles the request logic.

What Does the Server Do?

The server receives an HTTP request (usually passed from a front-end or web browser).

It passes the request to the WSGI application by calling it with

environandstart_response.The response from the application is then sent back to the client.

with make_server(host, port, application) as httpd:

print(f”✅ Server running on port {port}...”)

try:

httpd.serve_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print(”\\n🛑 Server stopped!”)

This creates the server and keeps it running.

httpd.serve_forever()keeps the server alive and listening.KeyboardInterrupt(Ctrl+C) gracefully shuts it down.

The code below builds our web application. Let’s name this file simple_wsgi_app.py.

The application function takes two parameters:

environandstart_response.The

environdictionary contains information about the request. It provides the web application with the necessary information to process the request (such as path and method).the

start_responseparameter is a callable (function) that the application uses to start the HTTP response by setting:Status line (e.g.,

‘200 OK’,‘404 Not Found’)Response headers (e.g., content type, content length)

Before returning a response to the client, the application must inform the server of the response type and length. This is done by calling

start_response(status, headers).headersis an important component of this application.It consists of two key elements: the response type and the response length.

This tells the client what type of response will be returned and how long it will be.

The response is encoded before being returned to the client.

Using this information, clients like browsers can decode the response and render it correctly.

The response begins by specifying the response type and its length in bytes.

Then the actual response is returned to the client.

“”“

Simple WSGI Web Application

A basic WSGI application demonstrating:

- WSGI interface: application(environ, start_response)

- Request handling and routing

- HTML response generation

“”“

def application(environ, start_response):

“”“

Main WSGI application with basic routing

Args:

environ: Dictionary with request information

start_response: Function to set response status and headers

Returns:

List of bytes (response body)

“”“

path = environ[’PATH_INFO’]

method = environ[’REQUEST_METHOD’]

# Simple routing

if path == ‘/’:

return home_page(environ, start_response)

elif path == ‘/about’:

return about_page(environ, start_response)

elif path == ‘/contact’:

return contact_page(environ, start_response)

else:

return not_found_page(environ, start_response)

def home_page(environ, start_response):

“”“Home page handler”“”

status = ‘200 OK’

headers = [(’Content-Type’, ‘text/html; charset=utf-8’)]

method = environ[’REQUEST_METHOD’]

path = environ[’PATH_INFO’]

query_string = environ.get(’QUERY_STRING’, ‘’)

body = f”“”

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Simple WSGI App</title>

<style>

body {{ font-family: Arial, sans-serif; margin: 40px; }}

.info {{ background: #f0f0f0; padding: 15px; margin: 15px 0; border-radius: 5px; }}

nav {{ margin: 20px 0; }}

nav a {{ margin-right: 15px; color: #007acc; text-decoration: none; }}

nav a:hover {{ text-decoration: underline; }}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Welcome to Simple WSGI App</h1>

<div class=”info”>

<h3>Request Information:</h3>

<p><strong>Method:</strong> {method}</p>

<p><strong>Path:</strong> {path}</p>

<p><strong>Query String:</strong> {query_string}</p>

</div>

<nav>

<a href=”/”>Home</a>

<a href=”/about”>About</a>

<a href=”/contact”>Contact</a>

</nav>

<p>This is a simple WSGI web application demonstrating basic concepts.</p>

</body>

</html>

“”“

response_bytes = body.encode(’utf-8’)

headers.append((’Content-Length’, str(len(response_bytes))))

start_response(status, headers)

return [response_bytes]

def about_page(environ, start_response):

“”“About page handler”“”

status = ‘200 OK’

headers = [(’Content-Type’, ‘text/html; charset=utf-8’)]

body = “”“

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>About - Simple WSGI App</title>

<style>

body { font-family: Arial, sans-serif; margin: 40px; }

nav { margin: 20px 0; }

nav a { margin-right: 15px; color: #007acc; text-decoration: none; }

nav a:hover { text-decoration: underline; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>About This Application</h1>

<p>This is a simple WSGI web application that demonstrates:</p>

<ul>

<li>WSGI application interface</li>

<li>Basic URL routing</li>

<li>Request/Response handling</li>

<li>HTML generation</li>

</ul>

<nav>

<a href=”/”>Home</a>

<a href=”/about”>About</a>

<a href=”/contact”>Contact</a>

</nav>

</body>

</html>

“”“

response_bytes = body.encode(’utf-8’)

headers.append((’Content-Length’, str(len(response_bytes))))

start_response(status, headers)

return [response_bytes]

def contact_page(environ, start_response):

“”“Contact page handler”“”

status = ‘200 OK’

headers = [(’Content-Type’, ‘text/html; charset=utf-8’)]

body = “”“

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Contact - Simple WSGI App</title>

<style>

body { font-family: Arial, sans-serif; margin: 40px; }

nav { margin: 20px 0; }

nav a { margin-right: 15px; color: #007acc; text-decoration: none; }

nav a:hover { text-decoration: underline; }

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Contact Us</h1>

<p>Get in touch with us:</p>

<p><strong>Email:</strong> contact@example.com</p>

<p><strong>Phone:</strong> (555) 123-4567</p>

<nav>

<a href=”/”>Home</a>

<a href=”/about”>About</a>

<a href=”/contact”>Contact</a>

</nav>

</body>

</html>

“”“

response_bytes = body.encode(’utf-8’)

headers.append((’Content-Length’, str(len(response_bytes))))

start_response(status, headers)

return [response_bytes]

def not_found_page(environ, start_response):

“”“404 error page handler”“”

status = ‘404 Not Found’

headers = [(’Content-Type’, ‘text/html; charset=utf-8’)]

path = environ.get(’PATH_INFO’, ‘/’)

body = f”“”

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>404 - Page Not Found</title>

<style>

body {{ font-family: Arial, sans-serif; margin: 40px; text-align: center; }}

.error {{ color: #dc3545; }}

nav {{ margin: 20px 0; }}

nav a {{ margin-right: 15px; color: #007acc; text-decoration: none; }}

nav a:hover {{ text-decoration: underline; }}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h1 class=”error”>404 - Page Not Found</h1>

<p>The page <code>{path}</code> could not be found.</p>

<nav>

<a href=”/”>Home</a>

<a href=”/about”>About</a>

<a href=”/contact”>Contact</a>

</nav>

</body>

</html>

“”“

response_bytes = body.encode(’utf-8’)

headers.append((’Content-Length’, str(len(response_bytes))))

start_response(status, headers)

return [response_bytes]

if __name__ == ‘__main__’:

print(”Simple WSGI Application”)

print(”Run with: python wsgi_server.py”)

In this example, the application handles three simple routes: Home, About, and Contact. The routing is based on the URL path, which is extracted from the environ dictionary. Depending on the path, the request is forwarded to the appropriate function, each of which returns an HTML response.

response_bytes = body.encode(’utf-8’)

headers.append((’Content-Length’, str(len(response_bytes))))

start_response(status, headers)

An essential part of the response is the **headers**list. This contains metadata about the response, including:

The Content-Type (to tell the client how to interpret the response)

The Content-Length (to specify the size of the response body in bytes)

The HTML response is always encoded as bytes before being returned to the client. With the help of the headers, browsers and other clients can properly decode and render the response.

ASGI

ASGI stands for Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface.

It is a specification that defines how Python web servers and applications communicate.

ASGI is the spiritual successor to WSGI (Web Server Gateway Interface).

Unlike WSGI, which supports only synchronous HTTP requests, ASGI supports both synchronous and asynchronous operations.

It can handle multiple protocols such as HTTP, WebSockets, and other event-driven connections.

ASGI acts as a bridge between the web server (e.g., Uvicorn, Daphne, Hypercorn) and the Python framework/application (e.g., FastAPI, Starlette, Django with Channels).

It is async-first, meaning it can run many requests or connections at the same time without waiting for one to finish before starting another. This is done using asynchronous programming, which avoids blocking the server while waiting for tasks like database queries, file reads, or API calls.

Ideal for real-time applications like chat systems, live dashboards, and streaming services.

ASGI Code Example

async def app(scope, receive, send):

if scope[”type”] == “http”:

html_content = b”“”

<html>

<head><title>ASGIRef Example</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Hello from asgiref!</h1>

<p>This is served by the reference ASGI server.</p>

</body>

</html>

“”“

await send({

“type”: “http.response.start”,

“status”: 200,

“headers”: [

(b”content-type”, b”text/html; charset=utf-8”),

(b”content-length”, str(len(html_content)).encode(”utf-8”)),

],

})

await send({

“type”: “http.response.body”,

“body”: html_content,

})

Explanation

async def app(scope, receive, send):

Every ASGI app is a callable that takes three arguments:

scope→ A dictionary with connection info (protocol, path, headers, etc.).receive→ An async function you call to receive incoming events/messages (like request body chunks, WebSocket messages).send→ An async function you call to send events/messages back (like HTTP headers, body chunks, close signals).

The

asyncmeans this function can useawaitfor asynchronous I/O.

if scope[”type”] == “http”:

Scope is a dictionary that contains all the static connection metadata for a single request or connection.

It’s created once when the connection starts, before your app starts receiving data.

Unlike WSGI’s

environ(which is for HTTP only), ASGI’sscopeworks for multiple protocols:HTTP

WebSocket

Lifespan events (startup/shutdown)

scope[”type”]tells us what kind of connection this is:“http”→ normal HTTP request“websocket”→ WebSocket connection“lifespan”→ server startup/shutdown events

Here, we only handle HTTP requests (other types of protocols will be ignored).

html_content = b”“”

<html>

<head><title>ASGIRef Example</title></head>

<body>

<h1>Hello from asgiref!</h1>

<p>This is served by the reference ASGI server.</p>

</body>

</html>

“”“

This is the HTML page we’ll send back.

It’s prefixed with

b→ meaning it’s bytes, because ASGI expects bytes for all body data (not strings).In ASGI, all data sent in the body or headers must be in bytes, not Unicode strings.

await send({

“type”: “http.response.start”,

“status”: 200,

“headers”: [

(b”content-type”, b”text/html; charset=utf-8”),

(b”content-length”, str(len(html_content)).encode(”utf-8”)),

],

})

await send({...})sends a message to the server telling it:“type”: “http.response.start”→ “I’m starting an HTTP response”“status”: 200→ HTTP status code“headers”→ List of(name, value)bytes pairs:content-type→ tells browser this is HTMLcontent-length→ number of bytes in the body

This step is like calling

start_response()in WSGI — it tells the server what’s coming.

await send({

“type”: “http.response.body”,

“body”: html_content,

})

Flow of execution

ASGI server accepts a request.

It calls

app(scope, receive, send).Our code:

Checks if it’s HTTP.

Prepares the HTML.

Sends headers (

http.response.start).Sends body (

http.response.body).

Server delivers it to the client.